Finding Private Mason

In 2003 I was invited to the Smithsonian to attend the autopsy of Giles County, TN Confederate solider Isaac Newton Mason conducted by world-respected forensic anthropologist Dr. Doug Owsley. Later I was interviewed for a Discovery Channel feature. For travel expense reimbursement only I will present my original program to any interested group as time allows. Email dejavu159@gmail.com for details. These stories, used by permission, appeared in the Pulaski Citizen in 2002-03.

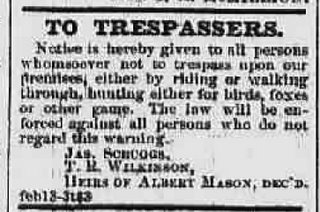

Monday, February 13, 2006

Giles County CSA Soldier Travels to Smithsonian

The reconstruction of Isaac Newton Mason's head is by John Gurche, an award winning paleo-artist whose work has appeared on the covers of National Geographic, Discover and Natural History Magazines and can be seen at the Smithsonian, the Field Museum and the American Museum of Natural History, among others. His work on the reconstruction of human ancestors has been featured in television documentaries by N ational Geographic, the Smithsonian, and the B

ational Geographic, the Smithsonian, and the B BC. He is well known for his work on the film "Jurassic Park" and for his paintings for the 1989 dinosaur stamps issued by the U.S. Postal Service. This photo by Smithsonian prhotographer Chip Clark is used with permission.

BC. He is well known for his work on the film "Jurassic Park" and for his paintings for the 1989 dinosaur stamps issued by the U.S. Postal Service. This photo by Smithsonian prhotographer Chip Clark is used with permission.

ational Geographic, the Smithsonian, and the B

ational Geographic, the Smithsonian, and the B BC. He is well known for his work on the film "Jurassic Park" and for his paintings for the 1989 dinosaur stamps issued by the U.S. Postal Service. This photo by Smithsonian prhotographer Chip Clark is used with permission.

BC. He is well known for his work on the film "Jurassic Park" and for his paintings for the 1989 dinosaur stamps issued by the U.S. Postal Service. This photo by Smithsonian prhotographer Chip Clark is used with permission.By CLAUDIA JOHNSON

Staff Writer

How I came to be present in the scientific research area of the Smithsonian’s Museum of Natural History when a 19th century iron burial case was opened by a team of prominent scientists started as a routine story for the Citizen/Press.

In covering the removal of the Mason Cemetery from Industrial Park South to Amos Hamlett Road, I prepared three stories. First, I covered the legal and logistical aspects of the move. Next, after six metal coffins were discovered, I prepared a story about burial cases and their local availability. Finally, after I had seen bones, coffins and the discolored earth where wooden caskets and Giles Countians once lay, I tried to answer the question, “Who were these people?”

As I related to Discovery Channel producer Kathy Abbott just before leaving DC on May 29, I approached these stories like a reporter. I researched, relied on old newspapers, court files and census records and consulted my historic resources like Clara Parker, Elizabeth White, Frank Tate and George Newman. I posted inquiries on the Internet’s genealogical sites, hoping someone would respond. Someone did. From Texas the wife of a Mason descendant emailed and introduced herself. In July Fran and Guy Mason visited the reconstructed cemetery and met with Nick Fielder, the state archeologist who had been in contact with the Smithsonian about examining the coffin.

Abbott explained that Discovery became involved when Harper-Collins was set to publish the book, No Bone Unturned, by Jeff Benedict, about forensic anthropologist Dr. Doug Owsley. Discovery had hoped to produce a show about Owsley, and everyone was urging that Discovery as well as another interested show, ABC’s 20/20, coordinate their Smithsonian visits with release of Benedict’s book.

The first I heard that the Smithsonian details were being ironed out was in mid-May when Fran Mason called from Texas saying she had forwarded my stories to the Smithsonian, and Owsley was interested in me being there when the coffin was opened and the body was autopsied for identification purposes. Since the grave marker was missing, there was some question as to whether the body was a Mason family member. The Smithsonian scientists believed they could confirm that.

Local attorney Stan Pierchoski was retained to prepare all application and

supporting documentation necessary to obtain a disinterment permit from the State Registrar upon receipt of a written affidavit signed by the next of kin, Guy Mason, and the person who is in charge of the disinterment, the state archeologist, as required by state law. No court order was required to obtain a disinterment permit for identification purposes.

supporting documentation necessary to obtain a disinterment permit from the State Registrar upon receipt of a written affidavit signed by the next of kin, Guy Mason, and the person who is in charge of the disinterment, the state archeologist, as required by state law. No court order was required to obtain a disinterment permit for identification purposes.Department of Health Policy Planning and Assessment Division of Vital Records attorney Richard Russell reviewed Pierchoski’s legal brief in support of the disinterment, and within 72 hours of taking the case Pierchoski had obtained the proper documents. Two days later the coffin was exhumed and on its way to Washington D.C. transported personally by Fielder and Steve Rogers of the Tennessee Historical Commission.

In the meantime Owsley had emailed me asking if I could make arrangements to be there on Wednesday, May 28. When I returned his call, I never imagined that Pulaski Publishing would actually send me to the Smithsonian, but the powers deemed it a worthy trip, and I was booked to fly out on May 27.

Owsley told me and my editor, Scott Stewart, that I was needed as the historic resource, but I made it clear that I am no historian, just a reporter who likes history and knows a lot of good sources.

“I’m a bone man,” he said. “To me, you’re a historian.” Bear in mind that at this point I had no idea I was talking to the man who identified the corpse of David Koresh and fit back together the parts of dozens of tragedy victims from the Branch Davidian Compound to Bosnia to the Pentagon on 9/11, where, incidentally, his daughter was working that day but was, thankfully, not a victim.

“I’m a bone man,” he said. “To me, you’re a historian.” Bear in mind that at this point I had no idea I was talking to the man who identified the corpse of David Koresh and fit back together the parts of dozens of tragedy victims from the Branch Davidian Compound to Bosnia to the Pentagon on 9/11, where, incidentally, his daughter was working that day but was, thankfully, not a victim.When I arrived Wednesday, May 28, at the Smithsonian, I was to report to security for a check of my briefcase, an official visitor’s badge and clearance for the winding trip through a confusing maze of hallways, stairs and elevators to a large third-floor examination room.

Teeming with television camera, sound and production crews from ABC and NBC and white-coated scientists, the central focus of the room was the simple cast iron burial case I’d last seen pulled from Giles County soil days earlier. Also present were Fran and Guy Mason, Fielder and Rogers, reporters from the Washington Post and USA Today, author Jeff Benedict, Smithsonian photographer Chip Clark and volunteers preparing laptop computers to type observations as researchers talked.

The rusted bolts securing top to bottom of the two-part case had been removed, with four left to be drilled out for TV cameras. After offering a brief overview of the project, explaining that he had only examined six metal coffins in his career and stating his expectations, Owsley introduced everyone in the room to television officials, even volunteers and research assistants, taking time to explain each person’s importance.

“This is the way you learn,” he said. “You learn best by doing.”

I was introduced as representing Giles County, invited as a historic reference as questions arose that required viewing against their historic backdrop.

With excitement we gathered around the table, as the preceding bustle took on a reverential air. Everyone was aware that a real person was inside the casket, a person buried 141 years earlier.

“Our primary obligation is to this individual,” Owsley said, and in silence the lid was hoisted and the body exposed.

Owsley motioned for Fran Mason and me to move in closer.

I am no relation to the man in the coffin and whether it was or was not proven to be Isaac Mason was of no consequence to me. However, as a person who loves history and Giles County, the fact that this man was one of us afforded me a connection that no other person in the room, not even the distantly blood-kin Masons, could know.

This was a young man of the first generation to be born in Giles County. He was one whose family had cleared the cane and worried of Indian attacks and buried loved ones killed by disease. Like numerous other early Giles Countians, he had worked and prospered and survived the county’s first half century only to see his homeland invaded and occupied by Union soldiers. Like many able young men of his time, he enlisted in the service of the Confederacy and left his home and family in effort to preserve their lives. For that, he returned home for burial in the family cemetery.

This man in the coffin died before this 35th birthday, and only two of his six children lived to adulthood. His wife remarried, and his property, after being pillaged by federal forces, became the home of others. In actuality, he was no different than hundreds, thousands of other Giles Countians, except it just so happened that his grave was moved and his rare coffin was intact and the Smithsonian wanted to study him.

Finding Private Mason: Confederate Soldier's Metal Coffin Opened at Smithsonian

In 2002 when I began covering relocation of the Mason Cemetery, I never imagined that a year later I’d be in the Smithsonian Institution as the remains believed to be that of planter and Confederate soldier Isaac Newton Mason was examined by a team of experts in forensic anthropology, forensic pathology and historic costuming. This was the first in a series of stories in upcoming issue of the Citizen/Press focusing on how the discovery of a cast iron coffin will bring Giles County to the attention of the nation on the television news program, 20/20 on Aug. 1 and a Discovery Channel documentary called "Skeleton Clues" featured during July 2003. I was interviewed by the documentary producer and parts of that interview appeared in the special, which is still airing as an occasional rerun on Discovery Channel. (photo by Chip Clark)

By CLAUDIA JOHNSON

Staff Writer

Early in 2002 the Giles County Economic Development Commission began the legal process of removing an abandoned cemetery from the center of a large tract of land in Industrial Park South on Highway 31 South to an area 1000 feet northwest alongside Amos Hamlett Road.

An archeological firm was hired to identify grave locations and exhume the remains from the 200-foot by 150-foot cemetery. In addition to the 22 marked graves, archeologists found 17 unmarked burials. Known as the Mason Cemetery because of its location on property owned by the Mason family for decades in the 19th century, the burial site was used for some 50 years with the last marked burial in 1875.

Many of the stones and box tombs were in deplorable condition from years of neglect. One of those had only the base of a headstone, which is not unusual in old unkempt cemeteries.

Situated among with the marked graves of early Giles Countians Isaac and Nancy Mason, their sons, daughters and grandchildren, the reasonable assumption was made that the grave was that of Isaac Newton Mason, who was born June 8, 1826, and died in the spring of 1862.

Situated among with the marked graves of early Giles Countians Isaac and Nancy Mason, their sons, daughters and grandchildren, the reasonable assumption was made that the grave was that of Isaac Newton Mason, who was born June 8, 1826, and died in the spring of 1862.From the surface I.N. Mason’s grave appeared no different that the thousands of graves in old cemeteries throughout the county. However, its contents will brought Giles County national attention when ABC’s 20/20 aired on Aug. 1, 2003, and a Discovery Channel documentary ran throughout the month of July, 2003.

Found in the grave was a cast iron coffin, which according to advertisements appearing 1850-60 editions of newspapers, were readily available from local furniture/undertaking establishments. At a time when wooden coffins cost a dollar or two, these lined and boxed burial cases, with designs ranging from plan to very elaborate could cost up to $53. In the Mason Cemetery, the cases were placed for burial inside their original wooden packing crates, which had disintegrated over the years, leaving only a rectangular-shaped “lens” of organic material around the cast iron coffin.

Five other heavy iron coffins were discovered in the Mason Cemetery containing the remains of three of I. N. Mason’s brothers and two of his nieces, but

only the one believed to be I.N. Mason was, after 140 years in the ground, still sealed and intact.

only the one believed to be I.N. Mason was, after 140 years in the ground, still sealed and intact.State Archeologist Nick Fielder reported the find to the Smithsonian Institution, and soon arrangements were underway to have it transported to the research facility for examination by Dr. Douglas Owsley, Curator of the National Museum of Natural History, his assistant, Karin Bruwelheide, Shelly Foote, Costume Historian of the National Museum of American History and Dr. Larry Cartmell, a forensic pathologist and amateur archeologist who has been testing South American mummies for nicotine and cocaine for more than a decade.

“We were asked to provide assistance with the identification of the individual contained in the coffin so that the members of the descendent family could properly mark the relocated burial,” states a report by Owsley, Bruwelheide and Foote in explanation of the Smithsonian’s interest in the coffin. “As few cast iron coffins have been examined and because this burial dated to the time of the Civil War, we agreed to provide assistance. The study was a rare opportunity to supplement our ongoing research on body preservation in historic period burials, burial customs of the 19th century and skeletal remains from the time of the Civil War.”

In May the Smithsonian was ready to open the coffin, examine the body and add findings to the institution’s extensive research databases. Since Owsley was the subject of a newly published book, No Bone Unturned, by investigative journalist Jeff Benedict, that captured the attention of 20/20 and Discovery, the timing clicked. Mason’s coffin would be opened in the presence of television cameras with only reporters from the Washington Post, USA Today and The Pulaski Citizen/Giles Free Press present.

And Owsley was just the man to open it.

Owsley, studied at the University of Tennessee under famous body-farm scientist, Bill Bass, and has worked with America's historic skeletons from colonial Jamestown burials to Plains Indians to Civil War soldiers to skeletons tens of thousands of years old.

The scientist has participated in landmark studies of 17th and 18th century U.S. colonies in Maryland and Jamestown, examined the ancient remains of the Spirit Cave mummy and the Kennewick man, both found in the United States and carbon dated to be nearly 10,000 years old.

Benedict’s book explores how Owsley became involved in a seven-year legal battle against the Justice Department and Indian tribes who claimed a 10,000 year-old Caucasoid skeleton found on a riverbank in Washington state was Native American and should be buried witho

ut being analyzed. Scientists worldwide joined Owsley in the a suit, and finally 2002 a federal court issued a landmark decision declaring that the federal government violated laws when it tried to bar Owsley from studying Kennewick Man.

ut being analyzed. Scientists worldwide joined Owsley in the a suit, and finally 2002 a federal court issued a landmark decision declaring that the federal government violated laws when it tried to bar Owsley from studying Kennewick Man.The decision will impact repatriation laws and have a significant impact on the classic views of “native Americans,” migration patterns, anthropology, as well as our understanding of pre-history, according to No Bone Unturned, which chronicles the case in depth and offers vignettes of Owsley’s other involvement with the federal government. Owsley is often enlisted by the State Department, the FBI and other federal agencies to identify remains. He and his scientific team have helped identify the remains of Bosnian war victims, American journalists murdered and burned in Guatemala, David Koresh’s remains and the other Waco victims and Pentagon victims from 9/11.

On May 28 he opened the coffin of a Giles Countian.

Who was Civil War solider Isaac Newton Mason

-Smithsonian photo by Chip Clark

-Smithsonian photo by Chip ClarkDr. Doug Owsley shows Pulaski Citizen staff writer Claudia Johnson how he learns about ancient people by reading their bones. These are the bones of Giles County planter and soldier Isaac Newton Mason who died in 1862.

story by CLAUDIA JOHNSON

Staff Writer

Of the six metal caskets found in 2002 during the relocation of the Mason Cemetery only the one believed to be Isaac Newton Mason remained sealed and intact. Although a portion of the tombstone was missing, the body was buried directly beside I.N. Mason’s parents and in a metal burial case like three of his brothers.

A research team assembled by the Smithsonian Institution has tentatively confirmed that the body was that of I.N. Mason based upon forensic evidence coupled with historic research. The story was featured in a special segment of ABC’s 20/20 on Aug. 1, 2003, and in a full-length piece about forensic anthropologist Dr. Doug Owsley on Discovery during July 2003.

But who was Isaac Newton Mason?

Isaac N. Mason, the son of early Giles County settlers, was born June 8, 1826, to Isaac and Nancy Edwards Mason. He married Margaret Ewing Scruggs on Oct. 2, 1850. Born July 16, 1832, the bride had graduated from the Tennessee Conference Seminary in Columbia on June 8, 1849. County records show that in 1842 I.N. Mason purchased 500 acres of family land in what was then the 5th district of Giles County for $4,379.69 when his father died without a will. By the 1850 census, which listed him as a 23-year-old farmer with a 19-year-old wife, his real estate was valued at $4,000.

The 1860 census identified Isaac N. as a farmer whose real estate was valued at $19,299 and personal property valued at $23,865. In his household were wife Mary, 26, daughters Margaret Mary (Mollie) Mason, 8, Alice, 5, Anne, 3, and a son, Isaac, four months old. Little Isaac died at age 2 1/2 in June of 1851. Isaac and Margaret’s unnamed infant daughter was born and died April 30, 1856, according to her grave marker.

In December of 1861 I.N. Newton and his brother Albert A. Mason enlisted as privates in the 11th Tennessee Cavalry Battalion, 6th (1st) Tennessee Cavalry Regiment.

The Battle of Shiloh in which the Mason brothers found themselves in April 1862 was fought to keep the federal troops from taking over the Memphis and Charleston Railroad, a vital supply line for the Confederacy that ran from the Mississippi River at Memphis to the Atlantic Ocean at Charleston, S.C. On the way it passed through Corinth, Miss., Decatur, Ala., and Chattanooga before branching off into two lines, one going to Richmond, Va., and the second to Charleston, S.C., and Savannah, Ga., by way of Atlanta, Ga.

At Corinth, Miss., the Mobile and Ohio Railroad (M&O) and the Memphis and Charleston Railroad crossed paths. These two railroads connected the Confederate States of America from the Mississippi River to the Atlantic Ocean and to the Gulf of Mexico.

These railroad lines linked the Confederacy. They transported troops from the deep South to Virginia and moved guns, ammunition, tents, clothing, shoes and material manufactured in Richmond, Va., Knoxville and Prattville, Ala., to the armies in the field.

If the Confederacy was to have a chance to win the war, they had to keep these rail lines open. The following letter offers a glimpse into the situation in Mississippi in which Albert and Isaac Newton Mason and others in their company may have found themselves following the battle of Shiloh.

HDQRS. ARMY OF THE MISSISSIPPI, Corinth, Miss., April 29, 1862.

Brig.-Gen. MAXEY, Cmdg. at Bethel, Tenn.:

GEN.: The enemy having torn up the track 3 miles this side of Bethel [Station], I have ordered its repair. You will furnish the railroad working party with a guard of three or four mounted companies to protect them from any interruption by the enemy. You will please send proper reconnoitering parties on the roads leading from Bethel to Bolivar and to this place, to determine the best ones to be followed by you should you have to move in either direction, as already directed.

The cavalry force ought to keep you well advised of the movements of the enemy on your front and flanks. Could you not protect your position with some rifle pits, &c.?

Respectfully, your obedient servant,

G. T. BEAUREGARD, Gen., Cmdg.

P. S.--In marching to this place your infantry might follow the railroad, provided it be safe to do so; your artillery and wagons, guarded by one regiment of infantry, coming by the best route west of the railroad.

The Memphis to Charleston was lost in April 1862 when its eastern headquarters, Huntsville, Ala., was captured. The loss of Memphis and Corinth, Miss., completed the destruction of this east-west link.

If family accounts of Mason’s death are true, this may be the railroad instrumental in the demise of Mason.

There is some question about where Isaac N. Mason died. A Mason family Bible indicates that he died at age 36 near Corinth, Miss., on April 18, 1862, just days after the Battle of Shiloh. A old family letter recounted the story that he died as a result of injures in a train wreck near Corinth. In an 1867 Giles County Chancery Court case witnesses represented to the court that Mason died at his residence in April 1862.

However, local historians believe the story sworn to by his daughter, Mollie M. Nelson, who identified herself as the oldest living lineal descendant of I.N. Mason when she applied for the Southern Cross of honor on his behalf. Mollie states in the application that her father died from effect of fall from train near Iuka, Miss, in May of 1862 at hospital in Tuscumbia, Ala.

This “Mollie” was Margaret Mary Mason, born Nov. 4, 1851, who is listed in the Giles County marriage records as being married on Nov. 25, 1869, to John Layfette Nelson.

A 1867 Giles County Chancery Court case states that I.N. Mason died without a will and owning 1640 acres of land, 27 slaves, mules, cattle, hogs and farming equipment. Whatever the circumstances, for certain the Civil War was raging, and Giles County was alternatively occupied by one or the other of the contending armies. The courts of the county were closed, and military law was in force. Isaac’s widow ran the farm as best she could under the circumstances, and after her marriage to George W. McGrew on Sept. 3, 1863, they both managed the farm in the best manner they could.

In time much of Mason’s personal property was taken or destroyed by the federal army or the robbers and thieves that infected the county. Losses included 130 acres of corn, 60 head of hogs, six horses, four mules, 23 head of cattle, 26 stacks of fodder, two horse wagons and all farming implements. The chancery suit filed by Mason’s widow asked that a dower be laid off for her possession and that the administrator sell enough of the remaining land to pay the debts.

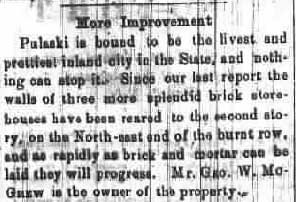

In the 1870 census Mollie is listed as a 19-year-old in the household of her mother and stepfather along with her husband, who was age 24, and was a clerk. This was possibly for Mollie’s stepfather, McGrew, (1815-1905), who was listed as a merchant with $100,000 worth of real and personal property. McGrew soon became very wealthy, but the Nov. 27, 1873, CITIZEN carried a large ad listing all his property for sale by the bankruptcy court.

I.N. Mason’s other daughters, Alice, 16, and Anne Mason, 13, also resided in the McGrew household in 1870. Anne did not survive to adulthood, but Alice married Thomas J. Flautt. Their daughter, Maggie, died young, but son Guy Mason Flautt, lived to adulthood marrying twice and producing one daughter, Joy Flautt.

In the 1880 census Mollie and J.L. Nelson’s household was listed separately with the following information: J. L. Nelson age 34, wife Mary M. Nelson age 25, son Henry Mason, age 9, son Edwin Erle, age 6, and son Isaac Floyd, age 2. Edwin Erle died in 1880 after the census was taken, according to his grave marker in Maplewood Cemetery. The Nelsons later had two other children, Andrew Chapel and Margaret Mai. Also buried in Maplewood are Mollie, who died in 1921 and her husband, who died in 1940.

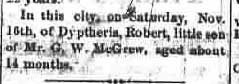

Isaac N. Mason’s widow died on Saturday, March 26, 1887. According to a newspaper account at that time, her health was feeble for several years, and in November 1885, she became worse. From that time until her death she was confined to her room and bed. After 16 months of “severe, uncomplaining suffering, she departed,” the Pulaski Citizen reported.

In June of 1910, as a result of Mollie Nelson’s application and endorsements by H.C. McLaurine, Neil McGrew and George T. Riddle, Isaac Newton Mason was awarded by the Giles County Chapter 257 of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, a Southern Cross of Honor, a Maltese Cross with a wreath of laurel surrounding the words "Deo Vindice (God our Vindicator) 1861-1865" and the inscription, "Southern Cross of Honor" on the face. On the reverse side is a Confederate Battle Flag surrounded by a laurel wreath and the words "United

Daughters of the Confederacy to the UCV."

Daughters of the Confederacy to the UCV."If conclusions drawn thusfar by scientsits and fortified by historic research are correct, while in Mississippi, Mason sustained a soft tissue injury that resulted in his being hospitalized and later dying in Tuscumbia, Ala. Was his brother Albert trying to bring him home to recover or just to die on his native soil?

Isaac’s fine broadcloth suit was slit to accomodate the physical changes caused by death and transport in the warm spring sun. His hand stitched boots remained on his feet when he was lovingly placed in the expensive iron burial case. Did his young widow choose his burial case from one of the local merchants? Her sister, who was married to Albert, had already buried two of her little daughters in similar but smaller cases. Albert and Isaac had buried their brothers, James and G.H., in metal cases. Could the family have anticipated that less than three years years later, Albert too would return to Giles soil for burial in the last of the metal coffins buried in the cemetery?

Isaac was laid to rest among family and extended family. On June 25, he was returned to the soil after a week in Washington D.C., and three days later Sons of Confederate Veterans, United Daughters of the Confederacy and Civil War reenactors honored him by the firing of a 21-gun salute and offering a final prayer that he rest in peace.

Isaac was laid to rest among family and extended family. On June 25, he was returned to the soil after a week in Washington D.C., and three days later Sons of Confederate Veterans, United Daughters of the Confederacy and Civil War reenactors honored him by the firing of a 21-gun salute and offering a final prayer that he rest in peace.Thanks to the following individuals who assisted with the historic and military research. Frank Tate, Clara Parker, Elizabeth White, Bob Wamble, Steve Rogers and George Newman.

Sidebar

I.N. Mason’s Civil War Service was short

The following information was compiled by Bob Wamble and used with his permission.

Enlisting in December of 1861, I.N. Newton was a private in the 11th Tennessee Cavalry Battalion, 6th (1st) Tennessee Cavalry Regiment.Lieutenant Colonel William Wallace Gordon's 11th Tennessee Cavalry Battalion was officially organized on Jan. 8, 1862, composed of six companies, including two from Giles County. At that time there were no cavalry commands large enough to be accepted into service as a regiment. Giles Countians served in this battalion.

Company A was organized by Captain James T. Wheeler, on December 9, 1861, with men from Giles County including private Isaac Newton Mason, according to information provided on a application for the Southern Cross of Honor.

Another company of Giles County men, Company B was organized by Captain William Wallace Gordon, December 10, 1861. Captain Gordon was promoted to the command of the battalion and replaced by Captain W. H. Abernathy. This battalion of cavalry was a short-lived organization and very little is known about its activities. This battalion was attached to the brigade commanded by Brigadier General W. H. Carroll of General Zollicoffer's command with whom it was regularly on duty and retired with Johnston's army to Corinth, Miss. It participated in the Battle of Shiloh, and was on outpost duty and scout services during all the arduous campaign from Shiloh to Corinth.

On April 28, 1862, the battalion with 32 officers, 357 men present for duty, 408 present and 469 present and absent, was reported in Brigadier General William N. R. Beall's Brigade in the Army of Mississippi, at Corinth, Miss.

In May 1862 at Corinth, Mississippi, the 2nd (Biffle's) and 11th (Gordon's) Tennessee Cavalry Battalions were consolidated to form the 1st Tennessee Cavalry Regiment. However, there was already a 1st Tennessee Cavalry Regiment in the Confederate Army and the official designation of this regiment was changed to the 6th Tennessee Cavalry Regiment. It continued to be known as the 1st Tennessee Cavalry in the field throughout the war, causing much confusion in its records.

The 6th Tennessee Cavalry Regiment was first commanded by Colonel Jacob Biffle. At the organization of the regiment, Lieutenant Colonel William Wallace Gordon was assigned to duty as Lieutenant Colonel but declined the position and resigned his commission.

The two companies of men from Giles County were now designated:

Company H - (formerly Co. B, 11th Bn) Captain Robert N. Jones.

Company K - (formerly Co. A, 11th Bn) Captain William O. Bennett. This was Mason’s Company, according to an article published in the Pulaski Citizen on Sept. 24, 1902. However, by order the Secretary of War, C.S.A, in July 1862, the regiment was reorganized and Giles Countian James T. Wheeler was elected Colonel. The regiment was known as Wheeler's 1st Tennessee Cavalry Regiment throughout the remainder of the war.

However, by that time Mason was already dead.

Albert Mason's daughter, Laura Mason Birdsong.

Albert Mason's daughter, Laura Mason Birdsong.

2002 Story Recalls How Mason Saga Began

By Claudia Johnson

Staff Writer

The relocation of a 19th century cemetery is underway in Giles County to make way for the future.

When Giles County began work on its Industrial Park South project, the Mason Cemetery was identified in an overgrown clump of trees on Amos Hamlett Road. Containing 22 grave stones in various states of disrepair, it had been abandoned and neglected. According to existing markers, the earliest burial was Henry Scales in 1839 and the last was Thomas Kellum in 1875. The oldest person was James Payne, who was born in 1771 and died in 1846.

Giles County Economic Development Director Robert Barnes said the existence of the 200-foot by 150-foot cemetery within the 45 acre industrial site began to present a problem. An initial survey was completed when Wal-Mart was eyeing the area for a possible distribution center.

“We had three industries who were looking for a large site,” Barnes said, explaining that correctly moving a cemetery takes time. “No company wants to wait a year for it.”

That’s why the industrial board decided to relocate the cemetery some 1,000 feet northwest to the corner of the industrial property. State laws protecting burial sites is very stringent, so following proper procedures is vitally important. Individuals with an interest in the cemetery had to located and contacted with respondents falling into three groups.

“The largest group said, ‘Thanks for the info, but we do not care to be involved,’” Barnes reported. “Another group encouraged the move. A few people were upset.”

Court orders and disinterment permits were obtained earlier this year, and archeologists are now conducting a methodical and well-documented move, which is expected to take several weeks.

The project is being coordinated by Dan Allen of DuVall and Associates. Allen holds a bachelor’s degree in anthropology with minors in archeology and history from Middle Tennessee State University, where he graduated with honors. He is currently a 2002 graduate candidate for master’s degree in history with an emphasis in cultural resource management.

He is a member of a number of state and regional archeological conferences and societies and has been involved in cemetery restorations and improvements and various historic sites across the state. He’s handled eleven major historic cemetery disinterments and relocations involving several hundred graves. More than 200 remains have been removed and relocated at prehistoric cemetery sites under Allen.

He has been the director for three years at the Summer Archaeology Camp at Belle Meade Plantation and for five years he served as Assistant Field Director, Middle Tennessee State University Archaeological Field School at Bledsoe's Fort in Sumner County.

Allen calls his craft “applied archeology,” explaining that he applies science to cemeteries while at the same time using his intuition and experience. Among the initial steps in relocating a cemetery are inventorying of the stones, identifying the location of each marked and unmarked grave and determining a cemetery’s true legal boundary as established by the Tennessee Code Annotated, which creates a 10 foot buffer zone around each grave.

Extensive documentation is created and maintained throughout the process. Allen and a crew of archeologists are on the site this week. The stones are labeled and have all been moved to the new cemetery site. A backhoe, which Allen is operating himself, is being used to scrape away one to two inches of soil so that the each grave shaft is exposed. After that, it’s hand tools only with one archeologist assigned to each grave.

Pulaski Publishing will continue this series as the cemetery removal progresses.

-staff photos by Claudia Johnson

Archeologists are now conducting a methodical and well-documented move of the Mason Cemetery, a 19th Century family burial plot believed to contain two dozen graves, from the middle of the new industrial park. Expected to take several weeks, the project will remove each marker and all grave contents to a designated area just off Amos Hamlett Road.

Smithsonian report: Mason may have died with his boots on far from home

Text and photos by CLAUDIA JOHNSON

Staff Writer

On May 28 a room filled with scientists and historians awaited removal of a heavy lid from a heavy cast iron coffin containing what was believed to be remains of Giles Countian Isaac Newton Mason, a private in the 11th Tennessee Cavalry Battalion, 6th (1st) Tennessee Cavalry Regiment.

Because few cast iron coffins have been examined and because the burial dated to the time of the Civil War, Smithsonian scientists and historians were interested in the intact and sealed metal burial case unearthed when the 19th Century Mason Cemetery was relocated last year. They agreed to help identify the body.

There is some question about where Isaac N. Mason died. A Mason family Bible indicates that he died near Corinth, Miss., on April 18, 1862, just days after the Battle of Shiloh. An old family letter recounted the story that he died as a result of injures in a train wreck near Corinth. In an 1867 Giles County Chancery Court case parties represented to the court that Mason died at his residence in April 1862.

However, it is the story sworn to by his daughter, Margaret, who identified herself as Mollie M. Nelson, when she applied for the United Daughters of the Confederacy’s Southern Cross of Honor on his behalf that local historians believe. Mollie stated in the application that her father died “from the effect of fall from a train near Iuka, Miss., in May of 1862 at hospital in Tuscumbia, Ala.”

Findings of the scientific team that examined the clothing, body and other contents of the cast iron coffin support Mollie Nelson’s claim. Heading up the scientific investigation team was Dr. Douglas Owsley, curator of the National Museum of Natural History. Invited to conduct analysis of Mason’s clothing was Shelly Foote, costume historian of National Museum of American History. Their observations along with analysis by paleopathologist, Dr. Larry Cartmell, a general pathologist who studies diseases in ancient burials, create a profile of Isaac Newton Mason at the time of his death and burial.

When the lid was lifted, inside was a complete skeleton clothed in civilian attire. Foote noted that the black broadcloth frock coat was probably tailor-made, as its collar and lapels that show evidence of quilting curved to fit the shape of the jacket. The back of the coat had a vertical slit that was not part of its construction but was intentionally cut by scissors or a knife.

The coat was single breasted with three buttonholes and an additional buttonhole in one lapel. The second button from the bottom was still attached to the coat. The button was metal-based and thread-covered, matching the three other buttons found in the coffin. There was a slit in the left breast of the coat for a pocket, which had come loose. A seam was present at the coat’s waist with an additional center back-seam and curved seams on either side. Two metal buttons, once thread covered, were present on the back of the coat at the waist seam.

The sleeves of two-part construction were slightly shaped at the elbow. The skirt of the coat measured 18 inches and was designed with a center back vent opening with a turn-over hem and seam on either side of the center back. The coat would have been fully lined, but the lining had deteriorated and was represented by a mass of thread. There was a rectangular hole, 2 inches by 1 3/8 inch, in the right front skirt of the coat near its bottom that had been mended with a finished patch, which was found in the coffin.

Near the neck region of the skeleton was a tie with a band of taffeta. The inside of the band was a woven material, probably black silk. The bow part of the tie was silk with a woven stripe. The tie band, either padded or multi-layered, was pre-formed with the ability to tie additional fabric to it to form the front bow.

Loose masses of thread are present throughout the chest and back region and are believed to represent a deteriorated vest. The threads will be identified by microscopic examination but are tentatively identified as silk.

The man was wearing tailor-made wool trousers. The trousers’ inseam measured 31 inches and waist of 32 inches. The trouser front has a 5-button fly with an additional button at the top of the waistband and a concealed trouser fly. Two gilt-type buttons are present at the top of the posterior waistband, probably for suspender use.

An adjustable enameled buckle with two strips of fabric in place was present at the back of the trousers. The trousers were constructed with a center back seam and a pieced inset on either side of the waist, producing a relatively rectangular fit, and had buttoning side pockets. The seam edges were raw, which was not unusual with broadcloth, Foote said. The left back leg had a small piece of trouser missing from the posterior hem. The hem of the pant leg was adhering to iron oxide accumulation on the side of the coffin and separation of the pant leg from the coffin wall resulted in this small defect in the cloth.Adjacent to the defect in the posterior bottom portion of the pant leg is a slit that was made with a scissors or knife. The slit runs approximately 2 1/8", but the entire opening/slit combination is 4 3/8" long. The side seam of the right pant leg was intentionally opened almost its entire length, from the hem to approximately crouch level.

In addition to the tailor-made suit, the man was wearing a pair of hand-stitched leather boots. The boots had a very narrow instep with a comparatively high stacked heel with nine lifts. The widest part of the sole was 3 inches and the length of the boot was 10 inches from the end of the heel to the toe tip. The soles of the boots are hand-stitched and are characteristic of a more expensive type of boot. Both boots are missing a piece of leather on the front top of the boot that would have extended to the knee. The flap had been removed, probably by preference of the owner. The toe end was almost square but showed light rounding. The portion of the boot that rests over the toe slants steeply, leaving little room for the toes, characteristic of riding boots during the 1850s and 1860s.

This style of boot was typical for the Civil War period and was used by both Confederate military personnel and civilians, Foote reported, adding that it was not uncommon for soldiers to buy better quality boots and wear them in the field.

Scientists hypothesized that if Mason died in Alabama as his daughter indicated and was transported home, the length of time required for this transfer would have initiated the process of decomposition.

“There is no physical evidence of cause of death visible in the skeleton, although modification in the clothing and the presence of footwear support the man’s death away from home, with some period of time between death and burial,” stated the preliminary Smithsonian report. “The slit in the back of the suit coat would have simplified the process of inserting the arms into the coat and would have also broadened the coat if the body was undergoing initial stages of decomposition (e.g. bloating).”

Foote noted that is unusual to recover men’s shoes or boots in 19th century burials, and alterations in the trousers suggest the body was dressed for burial with the boots already in place.

“The open seam of the right leg of the trouser and the slit in the left leg of the trouser allowed insertion of the booted feet and legs with greater ease,” the report observed. “Putting these boots on the feet of a deceased individual would have been extremely difficult. It is more likely that the individual died with his boots on, and they were not removed.”

Examination Helped Confirm Mason's Identity

Preliminary findings were revealed in a draft copy of “Mason Cast Iron Coffin Investigation Summary” by forensic anthropologist, Dr. Douglas Owsley, and Karin Bruwelheide, a physical anthropologist for the National Museum of Natural History.

Story and Photo by CLAUDIA JOHNSON

Staff Writer

When the heavy cast iron lid was hoisted from the coffin of what was believed to be Isaac Newton Mason’s remains in the Anthropology Conservation Laboratory on the third floor of the Smithsonian Institution on May 28, the only sound was the mechanical whirring of television cameras and the occasional click-click of Smithsonian photographer Chip Clark’s shutter. I arrived early that morning during preparations by the scientific team and set-up by ABC and NBC, but the coffin had been moved into the lab a day earlier, having been brought from Tennessee in a state vehicle by State Archeologist Nick Fielder and Steve Rogers of the Tennessee Historical Commission. The anticipated moment came at 10 a.m. when the last antiquated bolts were removed, the lid was lifted and a perfectly preserved skeleton dressed in a dark broadcloth suit was exposed to human observation for the first time since the spring of 1862. When the casket was excavated and reburied during relocation of the old Mason Cemetery in 2002, it was sealed. However, after re-interment, the faceplate cracked, presumably by the weight of saturated earth after several recent floods, so it was drained in the lab by making a small hole in the bottom of the coffin prior to the May 28 opening. Scientists found that due to the water-filled environment of the coffin and exposure to air, little soft tissue was preserved, but body and head hair adhered to some of the bones. There was no odor other than the smell of stagnate water. Earlier, one of the scientists held a flashlight to the glass viewing plate for me to look into the still-sealed coffin, but the expected bare skull was not visible. The body had shifted, leaving the head and shoulders to the left of center. The lower jawbone was separated from the skull, and the upper skull had rolled back with eye sockets toward the upper end of the casket. Dr. Larry Cartmell, a paleopathologist from Ada, Oka., who has gained an international reputation as an expert in mummy hair research, collected samples, placing large pieces of soft tissue and strands of the fine brown head hair, two and one half inches long, and lighter-colored body hair into plastic specimen bags while extracting smaller tissue samples with swabs or syringes. This process took several hours, during which time top Smithsonian officials visited with Dr. Owsley explaining why the project was being undertaken and how the team was planning to proceed. Later he and other scientists noted how rare it is that the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution would appear in the research lab, let alone spend half an hour asking questions. The broadcloth suit appeared as though it would be hard to the touch as a layer of silt had settled over it when the water was drained. One official asked if he could touch the suit, and when granted permission noted how pliable the material felt. Much discussion was initiated by the leather boots on the body, which could be seen from anywhere in the room on the feet crossed at the ankles and wedged carefully into the casket’s narrow end. After the dignitaries cleared, the research team settled on how to best remove the body from the coffin. Carefully maneuvered onto a makeshift sheet fashioned of heavy plastic, the body was lifted with special attention not to disturb location of the bones. It was zipped into a body bag for transport to a radiology room where it was x-rayed and CAT scanned while we all went to the staff cafeteria to eat lunch. During this time all residue was removed from the bottom of the coffin using a large plastic cup. Each scoop was washed through sieves until buttons and buckles, tissue and hair samples and teeth emerged. Several hours later when the body was wheeled back into the lab Owsley, Bruwelheide and Cartmell began to identify Isaac Newton Mason. The scientists slowly removed the skull and pulled each bone from the clothing. Foote was eager to begin cleaning and examining the suit and boots. Don Kloster, a Smithsonian curator emeritus of military history with a specialty in military uniforms, stopped by to consult with Foote. The skeleton was in excellent condition and was uniformly black in color due to iron-sulphide staining, Owsley noted, adding that ribs and vertebral bodies displayed erosion from contact with the coffin floor. Observing characteristics of the skull and pelvis and the relatively large joints and teeth, scientists identified the body as male. Age was placed at 35-39 based on such factors as age-related features of the pelvis area and dental and bone pathology. Further identified as being white and of European ancestry based on features of the skull, he had a slightly squared chin and a slight overbite, as indicated by patterns of tooth wear and location of the lower jaw in relation to the cranium. His forehead was moderately low and sloping. Features of the skeleton indicate that this individual was above average in stature for the mid 19th century, approximately 5'10", but somewhat slight of build. Because the right clavicle was a little larger than the left and showed greater development of the muscle attachment sites and the right arm was longer and larger than the left, Owsley concluded that the man was right handed. When I left the lab late on Wednesday, Owsley and the other researchers were planning for a long night. I later found that Owsley often spends the nights in the Smithsonian, sleeping on the floor of his skull-filled office. When I returned the next morning, the autopsy was finished, the skull and teeth had been reassembled and the bones were being laid out for photographing and discussion among the scientists. All bones were present and intact. With the exception of slight degenerative changes like arthritis in some joints and vertebrae, no other evidence of disease or trauma was noted. There was no physical evidence of the cause of death.  Both Cartmell and Owsley mentioned the possibility of a soft tissue injury based on information provided by Mason’s daughter that her father died as a result of the fall from a train. Owsley took me aside to show me some of the forensic evidence that could help him positively identify Mason. Picking up pelvic bones he pointed out dark semi-circles on the inside of each side of the pelvis at the muscle attachment sites of the hip bones and legs as well as some of the shape features of the hip sockets. Pointing to vertebrae, each with a little lip-like extensions, Owsley explained that they were herniated and consistent with traumatic compression of the spine. “You know what this tells us?” he asked. “It tells us that this man was a horseback rider.” Owsley said the man did not routinely participate in heavy physical labor, but horseback riding was an activity in which he was long engaged. I mentioned to Owsley that Mason owned 1,640 acres by the time of his death, had 27 slaves and had been relatively wealthy, so riding to oversee his farm would have been a daily activity. “What crops did he grow?” Owsley wanted to know. I told him that people in the part of Giles County where Mason lived often raised cotton and probably some tobacco. “Corn?” the scientist asked. The only evidence I had of corn as a Mason crop was in an old lawsuit list of personal property taken or destroyed by the federal army and thieves that included 130 acres of corn, 60 head of hogs, six horses, four mules, 23 head of cattle, 26 stacks of fodder, two horse wagons and all farming implements. “I bet he ate a lot of corn,” Owsley said. “The sugar in corn is very hard on teeth.” Owsley said that in life the man in the coffin had suffered from severe periodontal disease, losing 11 teeth. The remaining teeth, most of which had fallen into the coffin, had heavy calculus deposits, periodontal abscessing, marked build-up on the tooth roots and in some cases, only a root or remnant of where a tooth had been. Before I left Washington, Owsley asked me to sit with him and his research intern, Skye Chang, to discuss the historical backdrop against which Mason would have lived in early Giles County. Chang is compiling all facets of the project into a final report that will also be featured on the Internet. As we talked Mason became real… flesh covered the bones. He was in the saddle, riding across soft rolls of land in his special cut leather boots and tailor made suit, his fine brown hair blowing as the warm Southern wind ruffled the rows of corn. Through the convergence of historic research and forensic science, I could see Mason, finally, and like Owsley, I knew that the man in the coffin was the Giles County planter, soldier, father and husband who had died too soon.

Both Cartmell and Owsley mentioned the possibility of a soft tissue injury based on information provided by Mason’s daughter that her father died as a result of the fall from a train. Owsley took me aside to show me some of the forensic evidence that could help him positively identify Mason. Picking up pelvic bones he pointed out dark semi-circles on the inside of each side of the pelvis at the muscle attachment sites of the hip bones and legs as well as some of the shape features of the hip sockets. Pointing to vertebrae, each with a little lip-like extensions, Owsley explained that they were herniated and consistent with traumatic compression of the spine. “You know what this tells us?” he asked. “It tells us that this man was a horseback rider.” Owsley said the man did not routinely participate in heavy physical labor, but horseback riding was an activity in which he was long engaged. I mentioned to Owsley that Mason owned 1,640 acres by the time of his death, had 27 slaves and had been relatively wealthy, so riding to oversee his farm would have been a daily activity. “What crops did he grow?” Owsley wanted to know. I told him that people in the part of Giles County where Mason lived often raised cotton and probably some tobacco. “Corn?” the scientist asked. The only evidence I had of corn as a Mason crop was in an old lawsuit list of personal property taken or destroyed by the federal army and thieves that included 130 acres of corn, 60 head of hogs, six horses, four mules, 23 head of cattle, 26 stacks of fodder, two horse wagons and all farming implements. “I bet he ate a lot of corn,” Owsley said. “The sugar in corn is very hard on teeth.” Owsley said that in life the man in the coffin had suffered from severe periodontal disease, losing 11 teeth. The remaining teeth, most of which had fallen into the coffin, had heavy calculus deposits, periodontal abscessing, marked build-up on the tooth roots and in some cases, only a root or remnant of where a tooth had been. Before I left Washington, Owsley asked me to sit with him and his research intern, Skye Chang, to discuss the historical backdrop against which Mason would have lived in early Giles County. Chang is compiling all facets of the project into a final report that will also be featured on the Internet. As we talked Mason became real… flesh covered the bones. He was in the saddle, riding across soft rolls of land in his special cut leather boots and tailor made suit, his fine brown hair blowing as the warm Southern wind ruffled the rows of corn. Through the convergence of historic research and forensic science, I could see Mason, finally, and like Owsley, I knew that the man in the coffin was the Giles County planter, soldier, father and husband who had died too soon.

Both Cartmell and Owsley mentioned the possibility of a soft tissue injury based on information provided by Mason’s daughter that her father died as a result of the fall from a train. Owsley took me aside to show me some of the forensic evidence that could help him positively identify Mason. Picking up pelvic bones he pointed out dark semi-circles on the inside of each side of the pelvis at the muscle attachment sites of the hip bones and legs as well as some of the shape features of the hip sockets. Pointing to vertebrae, each with a little lip-like extensions, Owsley explained that they were herniated and consistent with traumatic compression of the spine. “You know what this tells us?” he asked. “It tells us that this man was a horseback rider.” Owsley said the man did not routinely participate in heavy physical labor, but horseback riding was an activity in which he was long engaged. I mentioned to Owsley that Mason owned 1,640 acres by the time of his death, had 27 slaves and had been relatively wealthy, so riding to oversee his farm would have been a daily activity. “What crops did he grow?” Owsley wanted to know. I told him that people in the part of Giles County where Mason lived often raised cotton and probably some tobacco. “Corn?” the scientist asked. The only evidence I had of corn as a Mason crop was in an old lawsuit list of personal property taken or destroyed by the federal army and thieves that included 130 acres of corn, 60 head of hogs, six horses, four mules, 23 head of cattle, 26 stacks of fodder, two horse wagons and all farming implements. “I bet he ate a lot of corn,” Owsley said. “The sugar in corn is very hard on teeth.” Owsley said that in life the man in the coffin had suffered from severe periodontal disease, losing 11 teeth. The remaining teeth, most of which had fallen into the coffin, had heavy calculus deposits, periodontal abscessing, marked build-up on the tooth roots and in some cases, only a root or remnant of where a tooth had been. Before I left Washington, Owsley asked me to sit with him and his research intern, Skye Chang, to discuss the historical backdrop against which Mason would have lived in early Giles County. Chang is compiling all facets of the project into a final report that will also be featured on the Internet. As we talked Mason became real… flesh covered the bones. He was in the saddle, riding across soft rolls of land in his special cut leather boots and tailor made suit, his fine brown hair blowing as the warm Southern wind ruffled the rows of corn. Through the convergence of historic research and forensic science, I could see Mason, finally, and like Owsley, I knew that the man in the coffin was the Giles County planter, soldier, father and husband who had died too soon.

Both Cartmell and Owsley mentioned the possibility of a soft tissue injury based on information provided by Mason’s daughter that her father died as a result of the fall from a train. Owsley took me aside to show me some of the forensic evidence that could help him positively identify Mason. Picking up pelvic bones he pointed out dark semi-circles on the inside of each side of the pelvis at the muscle attachment sites of the hip bones and legs as well as some of the shape features of the hip sockets. Pointing to vertebrae, each with a little lip-like extensions, Owsley explained that they were herniated and consistent with traumatic compression of the spine. “You know what this tells us?” he asked. “It tells us that this man was a horseback rider.” Owsley said the man did not routinely participate in heavy physical labor, but horseback riding was an activity in which he was long engaged. I mentioned to Owsley that Mason owned 1,640 acres by the time of his death, had 27 slaves and had been relatively wealthy, so riding to oversee his farm would have been a daily activity. “What crops did he grow?” Owsley wanted to know. I told him that people in the part of Giles County where Mason lived often raised cotton and probably some tobacco. “Corn?” the scientist asked. The only evidence I had of corn as a Mason crop was in an old lawsuit list of personal property taken or destroyed by the federal army and thieves that included 130 acres of corn, 60 head of hogs, six horses, four mules, 23 head of cattle, 26 stacks of fodder, two horse wagons and all farming implements. “I bet he ate a lot of corn,” Owsley said. “The sugar in corn is very hard on teeth.” Owsley said that in life the man in the coffin had suffered from severe periodontal disease, losing 11 teeth. The remaining teeth, most of which had fallen into the coffin, had heavy calculus deposits, periodontal abscessing, marked build-up on the tooth roots and in some cases, only a root or remnant of where a tooth had been. Before I left Washington, Owsley asked me to sit with him and his research intern, Skye Chang, to discuss the historical backdrop against which Mason would have lived in early Giles County. Chang is compiling all facets of the project into a final report that will also be featured on the Internet. As we talked Mason became real… flesh covered the bones. He was in the saddle, riding across soft rolls of land in his special cut leather boots and tailor made suit, his fine brown hair blowing as the warm Southern wind ruffled the rows of corn. Through the convergence of historic research and forensic science, I could see Mason, finally, and like Owsley, I knew that the man in the coffin was the Giles County planter, soldier, father and husband who had died too soon. Metal Coffins Were Expensive But Available in 19th Century

By Claudia Johnson

Staff Writer

- staff photo by Claudia Johnson

The metal burial cases, which began to be used in Giles County in the 1850s, redefined the terminology of dead body containers away from the harsh connotations of “coffins." The mummy-shaped cases had luxurious silk lining materials, glass viewing windows for the face or the entire corpse and individualized nameplates and varied in length from 22 inches to six and one half feet. Several of the cases were unearthed during the removal of bodies from the Mason cemetery, including one very fancy case molded to appear shroud-draped. All but one of the caskets had cracked or broken.

The recent excavation and relocation of more than three dozen bodies from the Mason Cemetery in the new industrial park has sparked interest regarding burial customs in 19th Century Giles County.

In the early days of the county before undertaking became a business coffins were made by carpenters and usually cost $1.50 a piece, the price for the man's work, according to Tom Carden in his 1904 articles on the history of the Pisgah community. A winding sheet and veil were the furnishings for the corpse.

Initially, Giles County undertakers were also furniture makers who advertised custom coffins and hearse services in local newspapers. Pulaski furniture maker C.W. Cofer advertised in the Feb. 21, 1850, edition of a local newspaper, The Western Standard, that coffins “will be made either fine or plain according to order on reasonable terms.” Cofer assured “those who patronize him” that had “a fine hearse” and would be “well prepared at all times to attend burials at the shortest notice possible.”

Frazier and Lytle purchased Cofer’s furniture company in 1852 and continued to operate the business on the south side of Madison Street, a few doors from the southwest corner of the public square. They advertised custom made coffins and use of a hearse in the Oct. 20, 1852, Democrat.

Carden noted that in 1854 there was an epidemic of dysentery, called brown flux, which killed people by the score, ofttimes almost exterminating large families. The historian told of the Sept. 2, 1854, death of Pisgah land owner Charles Pitts who was buried in a metallic coffin.

“I think it was the first coffin of that kind ever seen at this place,” Carden remarked. “It was the shape of a man and was copper lined and was very heavy. It is said to have looked very frightful.”

“I think it was the first coffin of that kind ever seen at this place,” Carden remarked. “It was the shape of a man and was copper lined and was very heavy. It is said to have looked very frightful.”

The Nov. 19, 1858, The Pulaski Citizen advertised the new furniture firm of Frazier and Mitchell, which had “the exclusive right to sell Crane’s world renowned patent metallic burial casket in Giles County.” Customers could choose from a selection “from fine to plain.”

By April 15, 1859, the firm’s advertisement in the Citizen identified the business as “dealers in furniture and chairs, and undertakers.” Wood coffins, both fine and plain, were “still made at short notice.” A hearse and horses were furnished free, and metallic burial caskets “of all sizes from infant’s to a grown person’s” were available. “To all who have seen these caskets, they need no recommendation from us” noted the advertisements.

James Mason, son of early settlers Isaac and Nancy Mason, died in December 1859 and was buried in the Mason cemetery in a fancy metallic case with a glass viewing panel. When archeologists working in the cemetery discovered the casket, the glass panel had collapsed against the body, preserving some of the blue suit in which he was buried. His brother, Albert, a Civil War solider, died in January 1865 and was buried in a very plain metal case, which archeologists unearthed. Several more of the cases were found during the removal of bodies from the Mason cemetery, including one very fancy case molded to appear shroud-draped. All but one of the caskets had cracked or broken.

His brother, Albert, a Civil War solider, died in January 1865 and was buried in a very plain metal case, which archeologists unearthed. Several more of the cases were found during the removal of bodies from the Mason cemetery, including one very fancy case molded to appear shroud-draped. All but one of the caskets had cracked or broken.

In the summer of 1859 a competitor in the furniture and funeral business, John J. Ducker, promised that “all orders for coffins will be promptly and speedily filled at any hour of the day or night and delivered to any part of the county at any specified hour” from his shop on the west side of the square.

“He has purchased a beautiful hearse, which together with a pair of gentle and reliable horses and a careful driver are at the command of all who patronize him in the undertaking business,” he promised, adding, “A share of the public patronage is most respectfully solicited.”

In June 8, 1860, Pulaski Citizen, A.L.& W.A. Crow announced that their stone cutting business on 3rd Main Street, South, would take “country produce, promissory notes, or in pinch, cash” in exchange for anything in their line. Work would also be given “in liquidation of any just debt.”

In the same Citizen issue George W. Woodring advertised a “fine assortment of monuments made of the finest statuary and Italian marble, and purchased in such a manner as to enable him to furnish them a great deal cheaper than they have ever been bought in this market before.”

He also promoted stone cutting, monuments and tombs of every description available at his stone yard on Second Main Street near the square “at cash prices for horses, mules or pork.”

At the onset of the Civil War Frazier and Mitchell advertised that they were the “only house in the county” that kept Crane’s Metallic Caskets.

Two and a half years after the Civil War ended, Sam C. Mitchell & Co., was advertising metallic and wood coffins, a “splendid hearse” and Mitchell’s undertaking services with “terms: cash.” While the style and expense of coffins had varied according to wealth even in colonial times, the 19th century witnessed a sustained era of coffin improvements. With the basic idea of storing a dead body within a closed container fairly well established, the improvements in the mid-nineteenth century aimed at a more protective and aesthetic device.

While the style and expense of coffins had varied according to wealth even in colonial times, the 19th century witnessed a sustained era of coffin improvements. With the basic idea of storing a dead body within a closed container fairly well established, the improvements in the mid-nineteenth century aimed at a more protective and aesthetic device.

The metal burial cases advertised in Pulaski in the 1850s had débuted in Providence, R.I., in the late 1840s. Cincinnati, Oh., stove- and hollowware manufacturers Crane, Breed & Co. purchased the Fisk Metallic Burial Case Company in 1853 and quickly began large-scale production.

These metal "cases" redefined the terminology of dead body containers away from the harsh connotations of "coffins." The mummy-shaped cases had luxurious silk lining materials, glass viewing windows for the face or the entire corpse and individualized nameplates and varied in length from 22 inches to six and one half feet. They were advertised as “thoroughly enameled inside and out” and purported to be "impervious to air and indestructible."

When properly secured with cement, Fisk's metallic cases were purported to be "perfectly air tight and free from exhalation of offensive gases."

The cases were advertised in large northern cities as "preserving in the most secure and appropriate manner, the remains of the dead from sudden decay, from water, from vermin and from the ravages of tee [sic] dissecting knife," drawing attention to the concern that grave robbers would remove bodies for study in medical schools, a common problem in the mid-19th Century.

In the early days of the county before undertaking became a business coffins were made by carpenters and usually cost $1.50 a piece, the price for the man's work, according to Tom Carden in his 1904 articles on the history of the Pisgah community. A winding sheet and veil were the furnishings for the corpse.

Initially, Giles County undertakers were also furniture makers who advertised custom coffins and hearse services in local newspapers. Pulaski furniture maker C.W. Cofer advertised in the Feb. 21, 1850, edition of a local newspaper, The Western Standard, that coffins “will be made either fine or plain according to order on reasonable terms.” Cofer assured “those who patronize him” that had “a fine hearse” and would be “well prepared at all times to attend burials at the shortest notice possible.”

Frazier and Lytle purchased Cofer’s furniture company in 1852 and continued to operate the business on the south side of Madison Street, a few doors from the southwest corner of the public square. They advertised custom made coffins and use of a hearse in the Oct. 20, 1852, Democrat.

Carden noted that in 1854 there was an epidemic of dysentery, called brown flux, which killed people by the score, ofttimes almost exterminating large families. The historian told of the Sept. 2, 1854, death of Pisgah land owner Charles Pitts who was buried in a metallic coffin.

“I think it was the first coffin of that kind ever seen at this place,” Carden remarked. “It was the shape of a man and was copper lined and was very heavy. It is said to have looked very frightful.”

“I think it was the first coffin of that kind ever seen at this place,” Carden remarked. “It was the shape of a man and was copper lined and was very heavy. It is said to have looked very frightful.”The Nov. 19, 1858, The Pulaski Citizen advertised the new furniture firm of Frazier and Mitchell, which had “the exclusive right to sell Crane’s world renowned patent metallic burial casket in Giles County.” Customers could choose from a selection “from fine to plain.”

By April 15, 1859, the firm’s advertisement in the Citizen identified the business as “dealers in furniture and chairs, and undertakers.” Wood coffins, both fine and plain, were “still made at short notice.” A hearse and horses were furnished free, and metallic burial caskets “of all sizes from infant’s to a grown person’s” were available. “To all who have seen these caskets, they need no recommendation from us” noted the advertisements.

James Mason, son of early settlers Isaac and Nancy Mason, died in December 1859 and was buried in the Mason cemetery in a fancy metallic case with a glass viewing panel. When archeologists working in the cemetery discovered the casket, the glass panel had collapsed against the body, preserving some of the blue suit in which he was buried.

His brother, Albert, a Civil War solider, died in January 1865 and was buried in a very plain metal case, which archeologists unearthed. Several more of the cases were found during the removal of bodies from the Mason cemetery, including one very fancy case molded to appear shroud-draped. All but one of the caskets had cracked or broken.

His brother, Albert, a Civil War solider, died in January 1865 and was buried in a very plain metal case, which archeologists unearthed. Several more of the cases were found during the removal of bodies from the Mason cemetery, including one very fancy case molded to appear shroud-draped. All but one of the caskets had cracked or broken.In the summer of 1859 a competitor in the furniture and funeral business, John J. Ducker, promised that “all orders for coffins will be promptly and speedily filled at any hour of the day or night and delivered to any part of the county at any specified hour” from his shop on the west side of the square.

“He has purchased a beautiful hearse, which together with a pair of gentle and reliable horses and a careful driver are at the command of all who patronize him in the undertaking business,” he promised, adding, “A share of the public patronage is most respectfully solicited.”

In June 8, 1860, Pulaski Citizen, A.L.& W.A. Crow announced that their stone cutting business on 3rd Main Street, South, would take “country produce, promissory notes, or in pinch, cash” in exchange for anything in their line. Work would also be given “in liquidation of any just debt.”

In the same Citizen issue George W. Woodring advertised a “fine assortment of monuments made of the finest statuary and Italian marble, and purchased in such a manner as to enable him to furnish them a great deal cheaper than they have ever been bought in this market before.”

He also promoted stone cutting, monuments and tombs of every description available at his stone yard on Second Main Street near the square “at cash prices for horses, mules or pork.”

At the onset of the Civil War Frazier and Mitchell advertised that they were the “only house in the county” that kept Crane’s Metallic Caskets.

Two and a half years after the Civil War ended, Sam C. Mitchell & Co., was advertising metallic and wood coffins, a “splendid hearse” and Mitchell’s undertaking services with “terms: cash.”

While the style and expense of coffins had varied according to wealth even in colonial times, the 19th century witnessed a sustained era of coffin improvements. With the basic idea of storing a dead body within a closed container fairly well established, the improvements in the mid-nineteenth century aimed at a more protective and aesthetic device.

While the style and expense of coffins had varied according to wealth even in colonial times, the 19th century witnessed a sustained era of coffin improvements. With the basic idea of storing a dead body within a closed container fairly well established, the improvements in the mid-nineteenth century aimed at a more protective and aesthetic device.The metal burial cases advertised in Pulaski in the 1850s had débuted in Providence, R.I., in the late 1840s. Cincinnati, Oh., stove- and hollowware manufacturers Crane, Breed & Co. purchased the Fisk Metallic Burial Case Company in 1853 and quickly began large-scale production.

These metal "cases" redefined the terminology of dead body containers away from the harsh connotations of "coffins." The mummy-shaped cases had luxurious silk lining materials, glass viewing windows for the face or the entire corpse and individualized nameplates and varied in length from 22 inches to six and one half feet. They were advertised as “thoroughly enameled inside and out” and purported to be "impervious to air and indestructible."

When properly secured with cement, Fisk's metallic cases were purported to be "perfectly air tight and free from exhalation of offensive gases."

The cases were advertised in large northern cities as "preserving in the most secure and appropriate manner, the remains of the dead from sudden decay, from water, from vermin and from the ravages of tee [sic] dissecting knife," drawing attention to the concern that grave robbers would remove bodies for study in medical schools, a common problem in the mid-19th Century.

Editor’s Note: Pulaski Publishing thanks genealogical researcher and author Frank Tate, George Newman of Giles County Historical Society, and Clara Parker and Elizabeth White of the Giles County Old Records Department for assistance with research, which utilized Giles County newspapers from the 19th century, early published local histories, genealogical records and old maps.

A Letter to the Pulaski Citizen from NBC/Discovery Channel

Dear Editor,

On Saturday, June 28, a funeral ceremony took place in Giles County to honor a man long lost to time and circumstance. Isaac Newton Mason was a Tennessee Calvaryman during the Civil War, who died in 1862. Originally buried in the old Mason Cemetery, the marker on his grave did not survive through the century. When all the graves were moved last year in anticipation of the new Industrial Park, he became a man without an identity. As recently chronicled in your paper by reporter Claudia Johnson, the rare cast-iron casket and the man inside embarked on a journey to the Smithsonian Institution this past May, where renowned forensic anthropologist Doug Owsley was able to confirm that he was, indeed, Isaac Newton Mason.

As a producer for NBC News Productions, I had the privilege of filming the identification effort for an upcoming Discovery Channel documentary. While the forensic side of the story was fascinating, it was important to me that I.N. Mason not be reduced to mere bones on a table. When I was told by Claudia Johnson that a ceremony for him was planned at the new cemetery sometime in the Fall, I was disappointed that I would not be able to include it in the documentary, since it would be a wonderful nod to his life and humanity. I was surprised and delighted when she told me that many folks in the community would be happy to put something together sooner.

In only a few short weeks, members of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, Sons of the Confederate Veterans and many Civil War re-enactors were able to do something truly extraordinary – plan a funeral appropriate for the man and the era. In the heatof that June morning, wearing heavy mid-1800 mourning clothes and uniforms, these dedicated people honored I.N. Mason with a ceremony befitting a Civil War solider and a son of Giles County. I was touched not only by the lovely proceedings, but by the incredible effort by all those involved. I would especially like to thank Tony Townsend of the Sons of the Confederate Veterans, who not only researched funerals of that time period for historical accuracy, but arranged to have a path cut to the cemetery to accommodate the horses ridden by the participants. And thanks to Cathy Wood, president of the local United Daughters of the Confederacy, who organized the women’s roles. The laying of Queen Anne’s lace and tiger lilies were touching moments during the ceremony. Although I could not attend myself, I am told that the procession over the hill and the 21-gun salute left few dry eyes at the grave site.