-Smithsonian photo by Chip Clark

-Smithsonian photo by Chip ClarkDr. Doug Owsley shows Pulaski Citizen staff writer Claudia Johnson how he learns about ancient people by reading their bones. These are the bones of Giles County planter and soldier Isaac Newton Mason who died in 1862.

story by CLAUDIA JOHNSON

Staff Writer

Of the six metal caskets found in 2002 during the relocation of the Mason Cemetery only the one believed to be Isaac Newton Mason remained sealed and intact. Although a portion of the tombstone was missing, the body was buried directly beside I.N. Mason’s parents and in a metal burial case like three of his brothers.

A research team assembled by the Smithsonian Institution has tentatively confirmed that the body was that of I.N. Mason based upon forensic evidence coupled with historic research. The story was featured in a special segment of ABC’s 20/20 on Aug. 1, 2003, and in a full-length piece about forensic anthropologist Dr. Doug Owsley on Discovery during July 2003.

But who was Isaac Newton Mason?

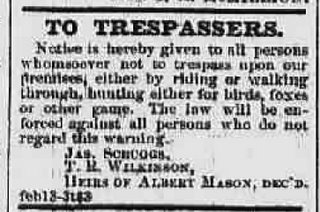

Isaac N. Mason, the son of early Giles County settlers, was born June 8, 1826, to Isaac and Nancy Edwards Mason. He married Margaret Ewing Scruggs on Oct. 2, 1850. Born July 16, 1832, the bride had graduated from the Tennessee Conference Seminary in Columbia on June 8, 1849. County records show that in 1842 I.N. Mason purchased 500 acres of family land in what was then the 5th district of Giles County for $4,379.69 when his father died without a will. By the 1850 census, which listed him as a 23-year-old farmer with a 19-year-old wife, his real estate was valued at $4,000.

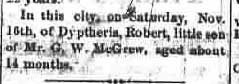

The 1860 census identified Isaac N. as a farmer whose real estate was valued at $19,299 and personal property valued at $23,865. In his household were wife Mary, 26, daughters Margaret Mary (Mollie) Mason, 8, Alice, 5, Anne, 3, and a son, Isaac, four months old. Little Isaac died at age 2 1/2 in June of 1851. Isaac and Margaret’s unnamed infant daughter was born and died April 30, 1856, according to her grave marker.

In December of 1861 I.N. Newton and his brother Albert A. Mason enlisted as privates in the 11th Tennessee Cavalry Battalion, 6th (1st) Tennessee Cavalry Regiment.

The Battle of Shiloh in which the Mason brothers found themselves in April 1862 was fought to keep the federal troops from taking over the Memphis and Charleston Railroad, a vital supply line for the Confederacy that ran from the Mississippi River at Memphis to the Atlantic Ocean at Charleston, S.C. On the way it passed through Corinth, Miss., Decatur, Ala., and Chattanooga before branching off into two lines, one going to Richmond, Va., and the second to Charleston, S.C., and Savannah, Ga., by way of Atlanta, Ga.

At Corinth, Miss., the Mobile and Ohio Railroad (M&O) and the Memphis and Charleston Railroad crossed paths. These two railroads connected the Confederate States of America from the Mississippi River to the Atlantic Ocean and to the Gulf of Mexico.

These railroad lines linked the Confederacy. They transported troops from the deep South to Virginia and moved guns, ammunition, tents, clothing, shoes and material manufactured in Richmond, Va., Knoxville and Prattville, Ala., to the armies in the field.

If the Confederacy was to have a chance to win the war, they had to keep these rail lines open. The following letter offers a glimpse into the situation in Mississippi in which Albert and Isaac Newton Mason and others in their company may have found themselves following the battle of Shiloh.

HDQRS. ARMY OF THE MISSISSIPPI, Corinth, Miss., April 29, 1862.

Brig.-Gen. MAXEY, Cmdg. at Bethel, Tenn.:

GEN.: The enemy having torn up the track 3 miles this side of Bethel [Station], I have ordered its repair. You will furnish the railroad working party with a guard of three or four mounted companies to protect them from any interruption by the enemy. You will please send proper reconnoitering parties on the roads leading from Bethel to Bolivar and to this place, to determine the best ones to be followed by you should you have to move in either direction, as already directed.

The cavalry force ought to keep you well advised of the movements of the enemy on your front and flanks. Could you not protect your position with some rifle pits, &c.?

Respectfully, your obedient servant,

G. T. BEAUREGARD, Gen., Cmdg.

P. S.--In marching to this place your infantry might follow the railroad, provided it be safe to do so; your artillery and wagons, guarded by one regiment of infantry, coming by the best route west of the railroad.

The Memphis to Charleston was lost in April 1862 when its eastern headquarters, Huntsville, Ala., was captured. The loss of Memphis and Corinth, Miss., completed the destruction of this east-west link.

If family accounts of Mason’s death are true, this may be the railroad instrumental in the demise of Mason.

There is some question about where Isaac N. Mason died. A Mason family Bible indicates that he died at age 36 near Corinth, Miss., on April 18, 1862, just days after the Battle of Shiloh. A old family letter recounted the story that he died as a result of injures in a train wreck near Corinth. In an 1867 Giles County Chancery Court case witnesses represented to the court that Mason died at his residence in April 1862.

However, local historians believe the story sworn to by his daughter, Mollie M. Nelson, who identified herself as the oldest living lineal descendant of I.N. Mason when she applied for the Southern Cross of honor on his behalf. Mollie states in the application that her father died from effect of fall from train near Iuka, Miss, in May of 1862 at hospital in Tuscumbia, Ala.

This “Mollie” was Margaret Mary Mason, born Nov. 4, 1851, who is listed in the Giles County marriage records as being married on Nov. 25, 1869, to John Layfette Nelson.

A 1867 Giles County Chancery Court case states that I.N. Mason died without a will and owning 1640 acres of land, 27 slaves, mules, cattle, hogs and farming equipment. Whatever the circumstances, for certain the Civil War was raging, and Giles County was alternatively occupied by one or the other of the contending armies. The courts of the county were closed, and military law was in force. Isaac’s widow ran the farm as best she could under the circumstances, and after her marriage to George W. McGrew on Sept. 3, 1863, they both managed the farm in the best manner they could.

In time much of Mason’s personal property was taken or destroyed by the federal army or the robbers and thieves that infected the county. Losses included 130 acres of corn, 60 head of hogs, six horses, four mules, 23 head of cattle, 26 stacks of fodder, two horse wagons and all farming implements. The chancery suit filed by Mason’s widow asked that a dower be laid off for her possession and that the administrator sell enough of the remaining land to pay the debts.

In the 1870 census Mollie is listed as a 19-year-old in the household of her mother and stepfather along with her husband, who was age 24, and was a clerk. This was possibly for Mollie’s stepfather, McGrew, (1815-1905), who was listed as a merchant with $100,000 worth of real and personal property. McGrew soon became very wealthy, but the Nov. 27, 1873, CITIZEN carried a large ad listing all his property for sale by the bankruptcy court.

I.N. Mason’s other daughters, Alice, 16, and Anne Mason, 13, also resided in the McGrew household in 1870. Anne did not survive to adulthood, but Alice married Thomas J. Flautt. Their daughter, Maggie, died young, but son Guy Mason Flautt, lived to adulthood marrying twice and producing one daughter, Joy Flautt.

In the 1880 census Mollie and J.L. Nelson’s household was listed separately with the following information: J. L. Nelson age 34, wife Mary M. Nelson age 25, son Henry Mason, age 9, son Edwin Erle, age 6, and son Isaac Floyd, age 2. Edwin Erle died in 1880 after the census was taken, according to his grave marker in Maplewood Cemetery. The Nelsons later had two other children, Andrew Chapel and Margaret Mai. Also buried in Maplewood are Mollie, who died in 1921 and her husband, who died in 1940.

Isaac N. Mason’s widow died on Saturday, March 26, 1887. According to a newspaper account at that time, her health was feeble for several years, and in November 1885, she became worse. From that time until her death she was confined to her room and bed. After 16 months of “severe, uncomplaining suffering, she departed,” the Pulaski Citizen reported.

In June of 1910, as a result of Mollie Nelson’s application and endorsements by H.C. McLaurine, Neil McGrew and George T. Riddle, Isaac Newton Mason was awarded by the Giles County Chapter 257 of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, a Southern Cross of Honor, a Maltese Cross with a wreath of laurel surrounding the words "Deo Vindice (God our Vindicator) 1861-1865" and the inscription, "Southern Cross of Honor" on the face. On the reverse side is a Confederate Battle Flag surrounded by a laurel wreath and the words "United

Daughters of the Confederacy to the UCV."

Daughters of the Confederacy to the UCV."If conclusions drawn thusfar by scientsits and fortified by historic research are correct, while in Mississippi, Mason sustained a soft tissue injury that resulted in his being hospitalized and later dying in Tuscumbia, Ala. Was his brother Albert trying to bring him home to recover or just to die on his native soil?

Isaac’s fine broadcloth suit was slit to accomodate the physical changes caused by death and transport in the warm spring sun. His hand stitched boots remained on his feet when he was lovingly placed in the expensive iron burial case. Did his young widow choose his burial case from one of the local merchants? Her sister, who was married to Albert, had already buried two of her little daughters in similar but smaller cases. Albert and Isaac had buried their brothers, James and G.H., in metal cases. Could the family have anticipated that less than three years years later, Albert too would return to Giles soil for burial in the last of the metal coffins buried in the cemetery?

Isaac was laid to rest among family and extended family. On June 25, he was returned to the soil after a week in Washington D.C., and three days later Sons of Confederate Veterans, United Daughters of the Confederacy and Civil War reenactors honored him by the firing of a 21-gun salute and offering a final prayer that he rest in peace.

Isaac was laid to rest among family and extended family. On June 25, he was returned to the soil after a week in Washington D.C., and three days later Sons of Confederate Veterans, United Daughters of the Confederacy and Civil War reenactors honored him by the firing of a 21-gun salute and offering a final prayer that he rest in peace.Thanks to the following individuals who assisted with the historic and military research. Frank Tate, Clara Parker, Elizabeth White, Bob Wamble, Steve Rogers and George Newman.

Sidebar

I.N. Mason’s Civil War Service was short

The following information was compiled by Bob Wamble and used with his permission.

Enlisting in December of 1861, I.N. Newton was a private in the 11th Tennessee Cavalry Battalion, 6th (1st) Tennessee Cavalry Regiment.Lieutenant Colonel William Wallace Gordon's 11th Tennessee Cavalry Battalion was officially organized on Jan. 8, 1862, composed of six companies, including two from Giles County. At that time there were no cavalry commands large enough to be accepted into service as a regiment. Giles Countians served in this battalion.

Company A was organized by Captain James T. Wheeler, on December 9, 1861, with men from Giles County including private Isaac Newton Mason, according to information provided on a application for the Southern Cross of Honor.

Another company of Giles County men, Company B was organized by Captain William Wallace Gordon, December 10, 1861. Captain Gordon was promoted to the command of the battalion and replaced by Captain W. H. Abernathy. This battalion of cavalry was a short-lived organization and very little is known about its activities. This battalion was attached to the brigade commanded by Brigadier General W. H. Carroll of General Zollicoffer's command with whom it was regularly on duty and retired with Johnston's army to Corinth, Miss. It participated in the Battle of Shiloh, and was on outpost duty and scout services during all the arduous campaign from Shiloh to Corinth.

On April 28, 1862, the battalion with 32 officers, 357 men present for duty, 408 present and 469 present and absent, was reported in Brigadier General William N. R. Beall's Brigade in the Army of Mississippi, at Corinth, Miss.

In May 1862 at Corinth, Mississippi, the 2nd (Biffle's) and 11th (Gordon's) Tennessee Cavalry Battalions were consolidated to form the 1st Tennessee Cavalry Regiment. However, there was already a 1st Tennessee Cavalry Regiment in the Confederate Army and the official designation of this regiment was changed to the 6th Tennessee Cavalry Regiment. It continued to be known as the 1st Tennessee Cavalry in the field throughout the war, causing much confusion in its records.

The 6th Tennessee Cavalry Regiment was first commanded by Colonel Jacob Biffle. At the organization of the regiment, Lieutenant Colonel William Wallace Gordon was assigned to duty as Lieutenant Colonel but declined the position and resigned his commission.

The two companies of men from Giles County were now designated:

Company H - (formerly Co. B, 11th Bn) Captain Robert N. Jones.

Company K - (formerly Co. A, 11th Bn) Captain William O. Bennett. This was Mason’s Company, according to an article published in the Pulaski Citizen on Sept. 24, 1902. However, by order the Secretary of War, C.S.A, in July 1862, the regiment was reorganized and Giles Countian James T. Wheeler was elected Colonel. The regiment was known as Wheeler's 1st Tennessee Cavalry Regiment throughout the remainder of the war.

However, by that time Mason was already dead.

Albert Mason's daughter, Laura Mason Birdsong.

Albert Mason's daughter, Laura Mason Birdsong.

No comments:

Post a Comment